Sherritt and the Indonesian Nickel Ban

I spent my free time during the last couple of days reviewing Sherritt International. I wanted to get some more clarity on my investment and come to a conclusion about the size of the position that I should have. As I have talked about in the past, my free time is limited and so my upfront research on names can be less than complete. I usually take small starter positions, between 1-3%, and then increase the size of those positions once I have had time to digest and review the idea in more detail.

As I tweeted last week, there were a number of catalysts that led me to take a position in Sherritt:

Took a position in Sherritt $S.CA – stock has been pummelled b/c of slow ramp of Ambatovy Ni mine, too much debt, low Ni/Coal prices (1/4)

— L.Sigurd (@LSigurd) January 17, 2014

I see # of catalysts. First, if Indonesia Ni export ban holds stockpiles will run down by some time in 15, see: http://t.co/cQShvQi7eQ (2/4)

— L.Sigurd (@LSigurd) January 17, 2014

Second, Ambatovy has struggled to get to commercial production but will pass milestone in Q1. Third, activist pushing from Clarke (3/4)

— L.Sigurd (@LSigurd) January 17, 2014

Fourth, sales of coal operations should dampen the “over leveraged” argument, provide flexibility, narrow focus to Ni and Oil (4/4)

— L.Sigurd (@LSigurd) January 17, 2014

After digging deeper into the name, the conclusion that I came to is that Sherritt is really a play on nickel. I think that as goes the price of nickel, so goes Sherritt.

Nickel Market Dynamics

Three months ago this would have been the end of the story. With all the uncertainty around the emerging markets these days, the thought of depending on worldwide nickel demand as the core of an investment thesis would have been unappealing. But there is a pretty interesting wild card being played into the nickel market right now, and that is the Indonesian ban on unrefined exports.

I was involved in the nickel market during the run up in prices during late 2006, early 2007. I remember riding up the literally parabolic rises of Lionore Mining and Rio Narcea Gold before both the companies were taken out. It was a fun time and anyone who is interested in reading about it should go back to the InvestorVillage RNO board, where fortunes were made and lost.

That party ended with the introduction of nickel in pig iron. When nickel ran up to $20/lb it triggered innovation, in particular the ability to smelt nickel out of low grade iron ore. At first this process was only profitable at high prices. If I remember right the marginal cost was something like $12/lb, but like most innovation, once the ball got rolling costs the cost curve continued to come down. According to a recent Sherritt presentation I read the costs are down to the $8 range now.

So nickel in pig iron now accounts for a significant portion of nickel supply. And most of that nickel in pig iron is mined in Indonesia. But while Indonesia produces the raw ore, they do none of the refining. The ore is shipped elsewhere (mostly to China) where the nickel is then extracted and sent off to the stainless steel manufacturers there.

Indonesia has tired of producing the low-end raw good and at the beginning of this year they implemented a ban on unrefined nickel. There seems to be a couple of exceptions to this ban; if the company is producing nickel as a by-product metal I have read that the ban does not apply, but it does apply to the vast majority of nickel production in the country.

I did some research into what this ban means for the nickel market. Basically, over the last year the nickel market has been in a rather severe state of surplus. In 2013 the surplus was 120,000 tonnes of nickel. Before the export ban the expectation for 2014, put forth in a forecast by the International Nickel Study Group, was that a similar surplus would exist in 2014. But here is the rub. Indonesia produced over 600,000 tonnes of nickel last year.

Now I haven’t been able to nail down exactly how much these numbers are going to drop this year. I know that China imports about 450,000 tonnes of nickel in pig iron, and that the majority of that comes from Indonesia. But the ban also includes concentrates, and I believe that most of the non-pig iron nickel that comes from Indonesia is still shipped outside the country in the form of concentrates for refining. So the hit to global supply is pretty significant.

The reason that the impact on the nickel price has been muted is that there is a large enough surplus of stockpiles right now to cushion the blow. But if the ban continues, this isn’t going to last. A number of analysts, including Commerzbank, Barclays, and Goldman Sachs, among others, have come out and said that the surplus will basically be depleted by either year end 2014 or early 2015. I thought there was a good take on the potential disruption in this BNN clip.

What I think

What I don’t like about investing in this situation is that it could change in a day if the Indonesian government backs down from their demands and starts to allow unprocessed nickel exports out of the country. And that is an entirely plausible scenario. Perhaps the muted response of the nickel price so far is in part because nobody believes that Indonesia will actually stick to their guns. They are losing revenue and presumably will begin to lose jobs if the ban continues. Whether they can stand the pain is an open question.

What I do like about this situation is that I honestly don’t think any of this is built into the share price of Sherritt. The stock is a little over $3.50, down by about half in the last year. If the ban is lifted I don’t think the share price does much of anything.

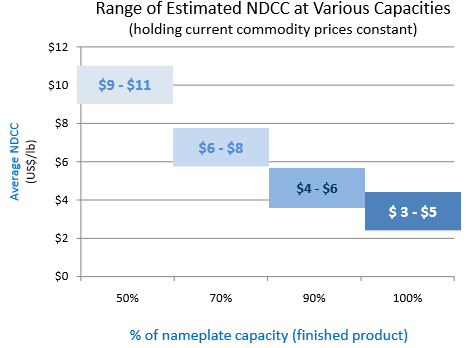

But if the ban sticks for any length of time, Sherritt will benefit. Sherritt produces 37 million pounds of nickel from its Moa mine in Cuba. They just announced commercial production from Ambatovy on Wednesday. Given that the capacity of Ambatovy is 132 million pounds, commercial production is 70% of capacity and Sherritt has a 40% stake in the mine, that is another 37 million pounds net to Sherritt. Its worth noting however that absent higher nickel prices Ambatovy production isn’t going to be terribly profitable until they can get capacity up to around 90%, see below:

With the sale of its coal assets Sherritt has become essentially a two trick pony. They have oil assets in Cuba and nickel assets in both Cuba and Madagascar. There are some other smaller oil assets elsewhere and some power generation assets in Cuba, but realistically the company goes as its primary oil and nickel assets go.

With the sale of its coal assets Sherritt has become essentially a two trick pony. They have oil assets in Cuba and nickel assets in both Cuba and Madagascar. There are some other smaller oil assets elsewhere and some power generation assets in Cuba, but realistically the company goes as its primary oil and nickel assets go.

The oil assets seem pretty stable. I balked at first at the reserve life index on their production (around 3 years) until it was pointed out in one of the presentations that the RLI has been 3 years for the last 20 years. Probably the bigger concern with the oil assets in Cuba are the renewal of existing blocks licenses that expire in 2018 and issuance of licenses of for new blocks to grow production. Sherritt has suggested they are well into negotiations and news may come some time in the first quarter. That might provide a boost to the stock.

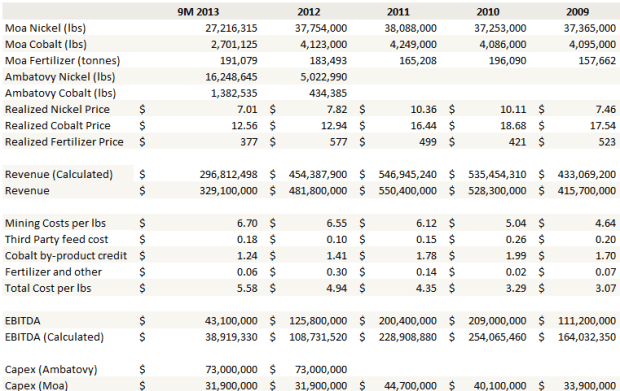

That leaves the nickel assets and in turn the rather long discussion that I have written about the future of Indonesian nickel production. Below I have reproduced the results from Sherritt’s metal segment over the last 5 years.

In 2010 and 2011, when nickel prices averaged around $10 per pound, the metals segment, which was basically the Moa mine, produced $200 million in EBITDA. At a little less than $8 per pound nickel, it produced $125 million. At $7 per pound, it is barely breaking even (though costs were temporarily escalated at Moa in 2013, which contributed to the EBITDA decline. Costs per pound were back down to $5.12 in the third quarter).

What becomes clear is how leveraged Sherritt is to the price of nickel, particularly after you consider that the table is really only including half (Moa) of current production (Ambatovy capitalizes revenue until it reaches commercial production) and that therefore nickel production will ramp to being double what it is here within the next year.

Conclusion

Sometimes I feel like I am writing the same story with different characters. This is an idea that is no sure thing. But there is a significant change/event where, if it plays out right, it will demand a step change in valuation and that is currently not baked into the price. I seem to run out this basic thesis over and over again with different names.

I’m not suggesting that Sherritt is a long term buy and hold that will inevitably generate positive returns over the long run. Mining is a tough business and the traditional nickel mining will continue to face tough competition from nickel in pig iron in the future.

But like most of my ideas, this is a situation where there is the chance of an upside surprise that does not appear to be priced into the stock and thus there is the potential for significant appreciation in the price of the stock if it is priced in. A continuation of the nickel export ban, a rise in the price of nickel, along with progress of Ambatovy and all of a sudden the dour estimates of barely breaking even are replaced by rosy projections of a profitable future. You don’t have to a firm conviction in the long-term price of nickel to understand that changes in perception influence stock prices, and that Sherritt could just as easily be justified as a $6 or $7 stock as it is now at $3 and change. On top of that you have an activist investor in Clarke Inc that is pushing the board for changes and so there is the potential for a positive outcome there.

I’m not convinced enough of the certainty of outcomes in Indonesia to add to my position. Its a little less than 3% position and its probably going to stay there unless I read something that changes my perspective on this. But that still would be a decent return for my portfolio if it does play out to a constructive end and I can sell my shares for let’s say $6. This would still put the stock well below its highs in 2011 (around $9), so it doesn’t seem too far-fetched.

Trackbacks & Pingbacks