Carry, Passive and a New Narrative

I am continuing to work through a new way of looking at the market and so this post will not talk very much about individual stocks.

In May or June, I started to realize that my framework for understanding the market was missing something.

I did not really know where to look for answers. All I knew was that the narrative that I was assuming drove the market could not be entirely right.

Before the virus, my simpleton view was that the market was going up because central banks were supporting it through easing, while the economy was not terrible. Together this led to expanding multiples and some growth – markets went up. But I also thought this was probably getting stretched, so I had my portfolio hedged.

Then the virus hit. Even though I saw the virus coming a little before most, and managed through it pretty well, I was surprised by just how fast and far markets moved down and then back up in its wake.

The word I kept using, somewhat unconsciously, was “tilt”. I kept saying to anyone who would listen, that this market is on tilt.

I don’t know why I chose that word. It just intuitively seemed kind of right. In retrospect, it was more apt than I realized.

Tilt is something that happens in pinball when you shake the machine. You basically force another factor into the game that the game was not designed for. It is no longer being played by the intended or agreed upon rules. In some sense, you have changed the game.

Are We on Tilt?

I know, I know, you can list a bunch of reasons to explain why the market has gone up.

There is the argument I made early on – that some stocks that are actually doing better because of the pandemic.

There is the argument that the stock market is made up of large companies, while the carnage caused by the pandemic is centered around small business. The biggest companies will take share.

There is the argument that the virus is not as bad as we thought.

And then there is the always present argument that central banks are storming the world with liquidity and that will lift all boats.

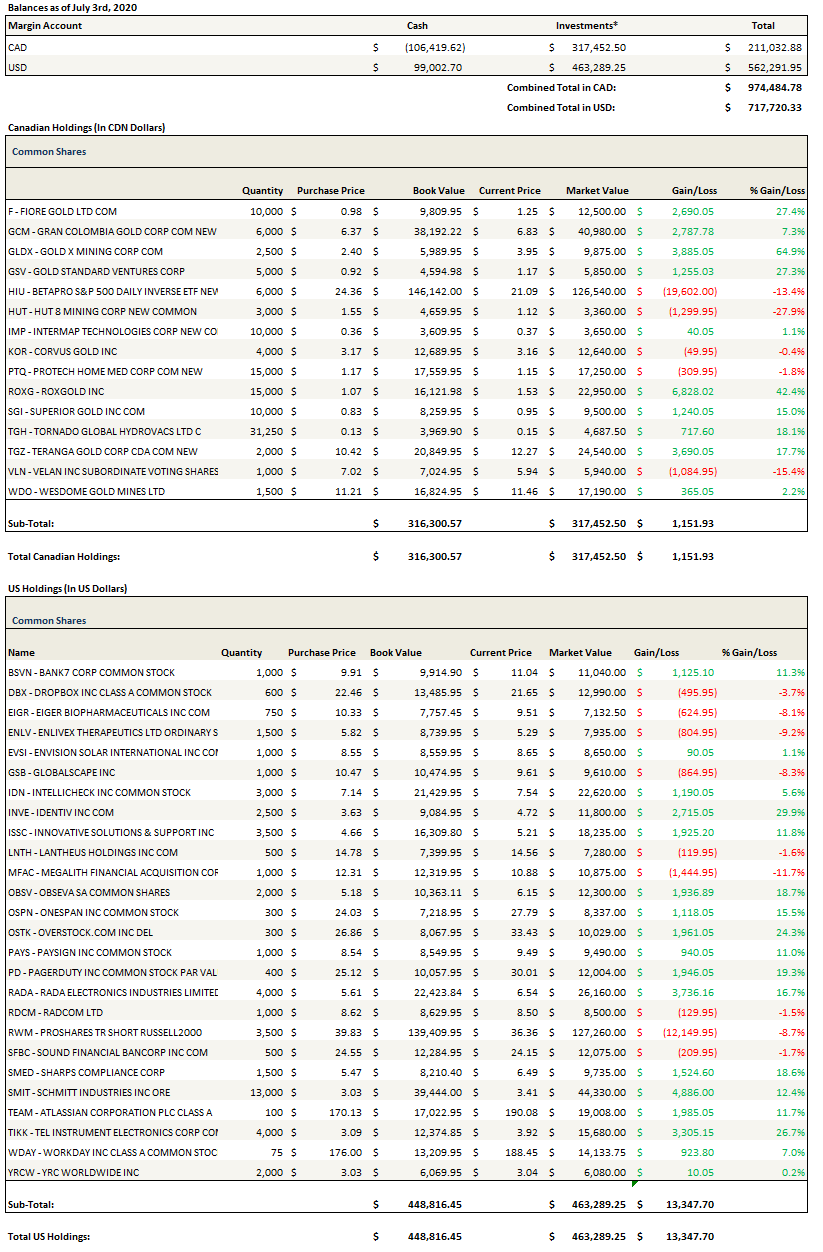

I realize all these things play a role. I have used them to varying degrees to inform my own stock decisions. I bought companies that were outperforming because the virus. I bought gold on the central bank narrative. I even sold short names like Ruths Chris, Spirit, and Delta and in June (no longer short any of these) because I didn’t really buy the whole virus is done argument – my opinion is that it has become largely irrelevant to stock prices as a whole – good for some names, bad for others.

But at the same time, I did not feel like these arguments, even taken together, explained what was happening. There had to be more to the puzzle – what was causing the tilt?

Wrapping My Head Around It

One question that I have always had, that has never really made sense to me, is this – if central bank money printing is causing asset bubbles, then why do the bubbles concentrate in some places and not others?

Why do stocks go up in one place or sector but in another they do not? Why do a few stocks garner most of the gains? Why do house prices go up some places and not others? Why don’t commodities just go up when equities are? Why doesn’t gold just go up?

In the past I have been fortunate to be introduced to important books or people at the right time. I started reading Basic Points, by Donald Coxe at the beginning of my investing journey (around ~2003) and he was the perfect voice for explaining the commodity boom in China. I stumbled on a book at the library by Richard Duncan in 2007 (The Dollar Crisis) which was an epiphany for me. I still believe it is the best explanation of the international monetary system out there at least for a beginner. The list is long.

In this case, I was lucky enough to have someone point out a book to me that helped illuminate the cause of our current tilt. The Rise of Carry may not be the best book on the subject (or maybe it is?) but for me it was an introduction to a whole other world.

Carry

There is a lot to say about carry and what I have learned so far. Many details and specifics, and maybe most interesting for me, the overlap with Duncan’s book – the two books essentially say the same thing from different directions.

But that is for another time. For now, just my aha moment. That carry trades do not depend on fundamentals.

Here I found my tilt.

The game we assume we are playing in the market is based on a rule that we take for granted. That the market discounts.

Apart from purely technical traders, when an active market participant is deciding to buy or sell a stock, there is some sort of discounting method that informs that decision. It could be a big spreadsheet, a simple P/E, maybe its just P/S, whatever.

But what if enough market participants begin to buy stocks for totally separate reasons? What if they are just making side bets?

These trades would be systematic. Their decision-making process would not consider the underlying “value” of what they are trading. They are making the trade because they expect it to be profitable of course. But those profits do not care about the value of what is being purchased or sold.

Carry trades care about market structure – the market must have a structure that makes these trades profitable. As long as that structure is there, these trades do not really consider the fundamentals that underly the trade.

Carry trades have been going on forever – I mean insurers and banks are essentially running carry trades.

Carry became more influential to markets in the 1990s. At the time it was mostly a currency phenomenon – the currency carry trade.

So carry is nothing new. But what is new-ish is how much of the carry trade now centers around the S&P 500. In The Rise of Carry, the authors call the S&P “the epicenter of the global carry trade”.

The authors argue that carry strategies now have enough influence on the S&P, through selling volatility and clipping the coupons, that carry to a large degree drives the S&P 500.

If that is true then the S&P is being driven in part by strategies that do not discount.

But carry trades are not the only market element that are trading systematically, without regard for discounting, and as a result putting the market on tilt. In fact, in the wake of my education on carry I was introduced to an even bigger participant.

Passive

I was lucky a second time to stumble on the right source. A couple of comments on the blog a few weeks ago mentioned Mike Green.

The funny thing about Green is that I have a subscription to RealVision. I have listened to a bunch of his interviews. He is a regular interviewer on the platform.

But I never really clued into what he was really saying. In the last few weeks, I have gone back and listened to or read the transcripts of pretty much every one of his interviews. They have taken on a new meaning to me.

Green talks about the carry trade himself – there is an interview he did with Andrew Scott where they describe the impact of Asian retail investing in retail structured products that was fascinating – but his main theme is the impact of passive investing.

Passive investing fit like a glove into the narrative I was already beginning to craft with carry.

This is an even more pervasive example of a market force that simply does not discount.

The logic of passive investing is so incredibly simple. If you give us money – we buy.

And it is big. Consider the following stats:

- Passive investing makes up ~43% of the US market right now

- More than 100% of gross flows into the stock market are passive

- People under 40 are highly passive investors while over 65 are active investors (20-25% passive)

- Nearly 85c of every incremental retirement dollar flows into a target dated fund

To me that seems like an awful lot of money that is pretty much ambivalent about what it is buying.

A New Narrative

So here we have a couple of legs on which to build a new narrative.

While I am still not sure about magnitude, I have some confidence that together, these strategies are quite influential. If that is right, there are some big implications.

The biggest of these implications is that the demise of discounting leads to a growing indifference to value.

I hate to get all philosophical, but I can’t think of a better way of saying it: value is existential. It only matters because we say it matters. If, at the extreme, every market participant is making their buying and selling decisions on some other criteria, then value, and valuation, has no meaning.

We are not at such an extreme, and I am not really sure we could actually get there, but we are moving in that direction, and that is enough to make a number of other inferences.

Others I can think of:

- Markets will become less responsive to economic conditions

- Markets, just in general, will become harder to move down (carry and passive inflows should be supportive most of the time) but when markets do move down, they move down harder and faster than in the past (because of A. the nature of carry and B. there are less active investors willing to “buy value”)

- Momentum will gain strength – what goes up should see more money go into it – ie. market cap weighted indexes naturally add to what is already strong

- A rise in correlation – securities are traded as a group. Differentiation that was brought on by discounting individual stocks is lost.

- Cash deployed – active cash is ~5% while passive cash is 10bps so more passive means more cash goes into the market – another support to the upside

- Increase in leverage – carry requires leverage and each reinflation of the carry trade is necessarily larger than the last.

- Domination by Vanguard/Blackrock – they have an outsized share of the passive market.

- Impact of obscure market players – stuff like how regulatory insurance requirements is driving, long dated put buying carry trades, Asian retail structured products as put sellers, how yield enhancement strategies dampen vol and then cause it to explode

There are others I am sure. I am still working through all of this and there are likely other very important pieces of the puzzle that I haven’t figured out yet.

What Now?

It is too bad that I did not realize this 4 months ago. It seems so obvious to me now that while I was hedging my portfolio with RWM and HUI.TO short index ETFs, I should have been hedging it directly with long vol.

Long volatility for a dumb retail guy like me simply means being long the VIX. I am not going to mess around with option strategies and the Greek alphabet. And like I have said before, the one great advantage of a retail schmo is that I have no benchmark, no expectation of performance. If I lose on the VIX for two years no one is around to care.

The VIX will lose money slowly until it makes it very fast. Consider that the VIX went from 10 to 100 in March. If I had been long that with the 25% of my portfolio instead of index shorts, I would have made a killing.

But going long the VIX right now does not seem like good timing.

We just had the carry crash. The market has tremendous support from the central banks, and as the authors of The Rise of Carry point out, central banks are the largest volatility sellers of all. Rates are likely to go lower, or at least stay low. Inflation is non-existent. Essentially all the elements that you can imagine upsetting the wheel cart have been pushed off the road.

Meanwhile the VIX is at 30. I would like to see it would fall back into the teens at least before all is said and done.

If anything, it seems more likely that we are at the beginning of another wave. Stocks only go up. I have been very twitchy, selling on the last couple of corrections, but each time I’ve been quick to buy it all back and more as things stabilize.

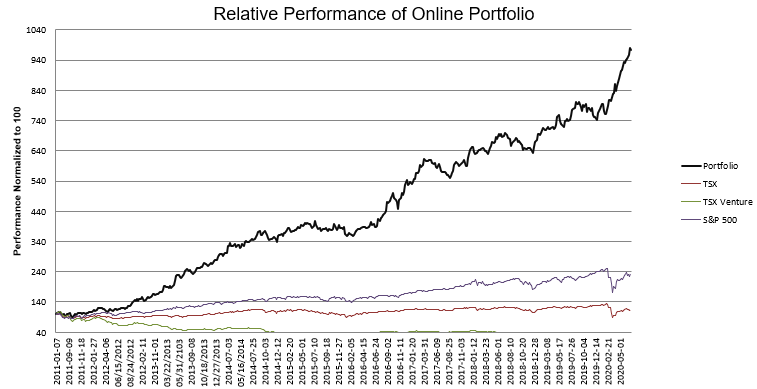

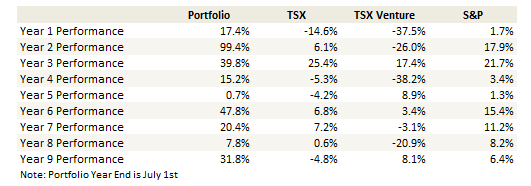

It is my way of getting comfortable with this new narrative. I am slowing coming around to believe it. First that happens in my head, and now its materializing in the portfolio.

With all that said, briefly on my positions: I added to Globalscape the last few weeks as I found the decline in the stock inexplicable. I added a new position in Novavax after reading a brokerage report by H.C Wainwright where they estimated 2021 earnings of over $12/share if the company is successful in their vaccine candidate. I also added another biotech name – Immunic.